HOME------FICTION------NON-FICTION------LOCALS------ABOUT![]()

Thickness Flow: The Larry Mayo Perspective

by Dan Reiter

for Eastern Surf Magazine

Photo: Nathan Adams

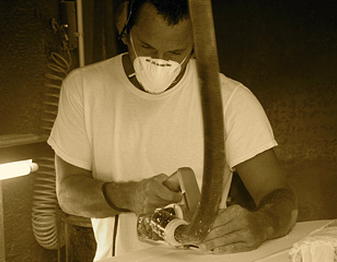

Somewhere at the southern edge of Cocoa Beach, Larry Mayo takes his caliper to a slab of US Blanks foam. The shaper is the same size as the blank––tanned, green-eyed, gloriously rustic, handsome in the way of the northern Italian paisano or the Frenchman of Provence. “The classic 6’2” C fish blank," Mayo says. “Blue foam.” The face of the slab is factory shorn, rough, pitted. He skids his hands over it. Somewhere in this block of foam, a stub-tail diamond quad is hiding.

Mow.

Mayo's planer drones like a siren, stings the ears. He cross-steps, barefoot, through two passes, blending his cut bands. “Flat rocker,” he says. “Fast and wide.” He checks his notes. “The kid wants three logos on the deck.” For some reason, this amuses Mayo.

Outline.

Mayo is shaper, sander, glasser, hot coat man. He laminates, tints, tapes, pinlines, embeds his own fin boxes. He pencil-marks the stringer, pulls in an eighth, lets out like a bespoke tailor. Traces curves along Masonite. Marries templates. “It will go,” he says. “Get on a plane quick.” Behind the jigsaw, foam dust on his arms and his feet, he shears away the edges, until only the board remains.

Sand.

"Turns out Greenough was right all along," Mayo says. "You fit the board to the wave." Foiling the vessel, peeling it clean as apple flesh. Student of the old new school. Take what you've learned and move on. At the Milwaukee grinder, sweeping it in flourishes, Mayo smooths the deck to fuzz, shaves stringer, curls wood, blends and blends until it is smooth as eggshell.

Cloth.

In a corrugated, mangrove-fringed marina on the Banana River, the glassing room has the look of a dojo: minimalist, clean, razor blades in the wall like throwing stars. “Another burgundy board,” Mayo says, unspooling the six-ounce Volan over his most recent sculpture. “Just when it stopped looking like a crime scene in here.” His scissors are a foot long. He slices the cloth with wrist-driven cuts.

Glass.

Coke-bottle greens, persimmons, saffrons, mosses. His tint jobs breed collectors, inspire fetishism. Straining the burgundy now, gentling it like a sommelier, Mayo meditates on viscosity and proportion, in respirator and rubber gloves, slicks his squeegee over his fish. Fresh-air fans inject cold air. He wants the foam contracting as he lacquers the resin over the Volan. This takes time. This is what Mayo Surfboards are about: time. The extra pass.

Hot Coat.

The crest of County Mayo, Ireland, features a rockered-out ship aroll on blue waves. His forbears, a maritime people. For his own shield, he employs a circle of psychedelic, cloud-patterned letters. Jimi Hendrix meets the White Album. He papers a single logo over the stringer. Elegant enough. Mayo does not put three logos on a deck.

A four-inch paintbrush for the hot coat. As if resin is pouring from his fingertips. The color resurrects. “The closer you get to the old school way," he says, "the better the job.”

Gloss.

Mayo has made it perfect, then sanded it down again. The board now has the matte finish of a red delicious apple. “You have to sand deep into the hot coat to get good clarity on the gloss coat," he says. Lost art in a spray finish age, the gloss coat––a residual of artisinal times, of muscle cars, Stratocasters.

Mayo pulls the hardener up through a straw with a chemist's touch. "A voodoo to glossing. It's volatile. You can't have oils or contaminants on the brush." He eases it on in long, sinuous strokes, the final coat, brings the board to an impossible, seductive shine. A '71 Porsche. "It's good when it locks up like that," Mayo says, smiling. "Right after it flows out."

Polish.

Mayo takes a grinder to the board, sands down the gloss coat with 320-grit Rhinolux paper. Switches out to 400 and hits it again. Sands it again with the 600. Mayo's hands have passed over every inch of this board, by my count, forty-three times. He blows the board clean, ties on his apron, brushes on the polish like an old country woodworker. Forty-four.

The buffer clocks around at 6000 rpm, riding the deck to Wilco's "Whole Love." The surfboard fulfills its own destiny. Mayo is just here to see it through. The true and final color: a vintage burgundy, pure and clean, sheened to mirror glass.

Mayo's reflection swims inside as he cross-steps into another pass.

![]()